Although the US has abandoned its policy of engagement with China, the strategy of great-power competition that has replaced it does not preclude cooperation in some areas. A good analogy is a soccer match, where two teams battle fiercely but abide by certain rules and boundaries, kicking only the ball, rather than each other.

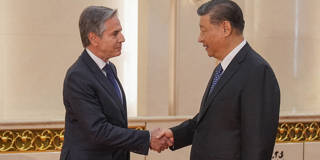

CAMBRIDGE – When US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently visited Beijing in an effort to stabilize relations with China, many of the issues that he discussed with Chinese President Xi Jinping were highly contentious. For example, Blinken warned China against providing materials and technology to aid Russia in its war against Ukraine, and he objected to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and harassment of the Philippines (a United States ally). Other disputes concerned interpretations of America’s “one-China” policy toward Taiwan, and US trade and export controls on the flow of technology to China.

I was visiting Beijing around the same time as the chair of a Sino-American “track two dialogue,” where citizens who are in communication with their respective governments can meet and speak for themselves. Because such talks are unofficial and disavowable, they can sometimes be more candid. That was certainly the case this time, when a delegation from the Aspen Strategy Group met with a group assembled by the influential Central Party School in Beijing – the sixth such meeting between the two institutions over the past decade.

As one would expect, the Americans reinforced Blinken’s message on the contentious issues, and the Chinese repeated their own government’s positions. As one retired Chinese general warned, “Taiwan is the core of our core issues.”

CAMBRIDGE – When US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently visited Beijing in an effort to stabilize relations with China, many of the issues that he discussed with Chinese President Xi Jinping were highly contentious. For example, Blinken warned China against providing materials and technology to aid Russia in its war against Ukraine, and he objected to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and harassment of the Philippines (a United States ally). Other disputes concerned interpretations of America’s “one-China” policy toward Taiwan, and US trade and export controls on the flow of technology to China.

I was visiting Beijing around the same time as the chair of a Sino-American “track two dialogue,” where citizens who are in communication with their respective governments can meet and speak for themselves. Because such talks are unofficial and disavowable, they can sometimes be more candid. That was certainly the case this time, when a delegation from the Aspen Strategy Group met with a group assembled by the influential Central Party School in Beijing – the sixth such meeting between the two institutions over the past decade.

As one would expect, the Americans reinforced Blinken’s message on the contentious issues, and the Chinese repeated their own government’s positions. As one retired Chinese general warned, “Taiwan is the core of our core issues.”